Rubbish

Conversation with Lars Tharp at the Hepworth, Wakefield, 10/01/14.

The

Hepworth ran an #ICollect

this weekend

with Lars Tharp and the Museum of Contemporary Rubbish booked

onto the Sunday morning session:

WHAT

IS IT WORTH?:

“Ever

wondered if you're sitting on a small fortune? Bring in one or two

objects from your ceramics, glass or oriental goods collection to

learn more from BBC Antiques Roadshow expert, Lars Tharp.”

As

Wikipedia details:

“Wikipedia Lars Broholm Tharp is a Danish-born historian, lecturer

and broadcaster, and one of the longest running 'experts' on the BBC

antiques programme, Antiques

Roadshow,

first appearing in 1986. [..]

He studied Archaeology and Anthropology at Gonville and Caius

College, Cambridge University.”

Archaeology

is, essentially, studying

old

rubbish and you cannot study rubbish without studying anthropology to

some degree, so this was a great opportunity to pick Lars' brains

about value, worth and rubbish.

I

arrived at The Hepworth, booked in and took my ticket. The Hepworth

staff were bemused by my collections and seemed also keen to see what

Lars said about the value. The social media guy found me, got some

pictures and we had a chat about rubbish in art. He recalled a show

he'd seen at the Hayward last summer The

Alternative Guide to the Universe with Congolese 'Outsider'

artist Bodys Isek Kingelez who makes models of fantastical cities out

of cardboard and discarded materials. Another one for the compendium!

Whilst

I waited my turn in the room I'd previously curated Pecha Kucha Night

Wakefield in a couple of years ago, Lars talked to other collectors

about their pictures, glass ornamental vases and the like. People

were beginning to fill up the space and as my turn was called he

announced he would be speeding up the proceedings to fit everyone in.

The following 10 minutes of conversation are transcribed below:

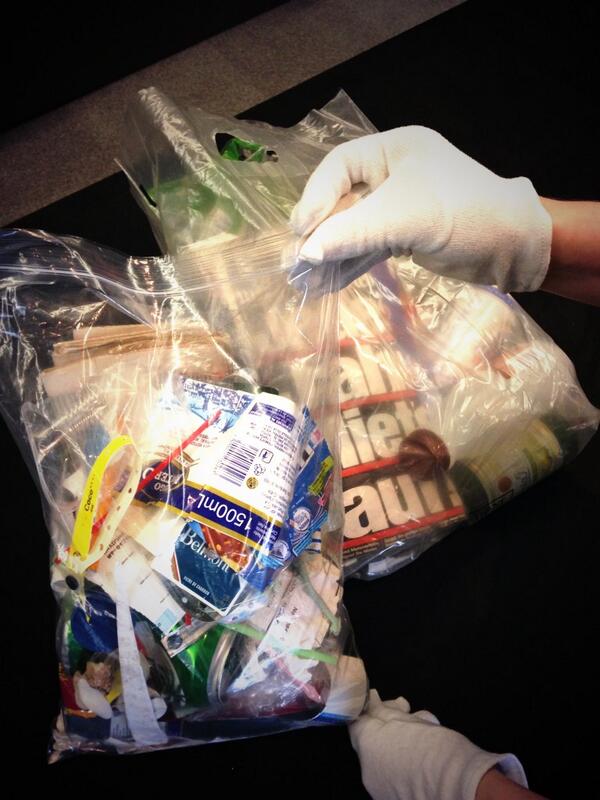

|

| Photo courtesy The Hepworth, Wakefield |

Lars

Tharp: You've brought in an installation. This is what I'd call an

installation.

Alice

Bradshaw: This is the Cuba Collection and this one is from Essen in

Germany.

LT:

How did these come about?

AB

This one [The Cuba Collection] was collected by myself whilst I was

over there on holiday and this one [The Essen Collection was sent

over by a musician friend as part of a Ruhr

Valley-Calder Valley exchange.

LT:

OK. This is the first time I've ever seen a collection like this.

This is basically someone's rubbish bin, isn't it?

AB:

Yes, this one [The Essen Collection] is, but this one [The Cuba

Collection] is from all over parts of Cuba; from Havana and the Cayo

Coco Islands.

LT:

This is the sort of thing that would have made it into the Opie

Collection. He specialises in packaging and the history of

packaging. His Museum used to be in Gloucester but now it's in London

in storage because it's so massive.

So

what you've brought is a time capsule. Is it just one person's

rubbish?

AB: No

it's multiple people's; found on the beach and on the street. But

this [The Essen Collection] is one person's rubbish and these are

just two collections from the entire Museum of Contemporary Rubbish.

LT:

What a great name! The Museum of Contemporary Rubbish. Where does

that hang out?

AB: It

exists online. Most of the Collections are recycled and there's only

a couple of Collections that still exist in physical form. I document

every single item and the blog features all the items and

Collections.

LT:

Now, what do you regard yourself as an anthropologist or as an

artist?

AB: As

an artist, but there's certainly an anthropological inclination to my

work.

LT:

I've got a couple of books back there on collecting and the theory of

collecting. I was reading a particular book yesterday; basically a

very Marxian approach to why we collect things and why we have to own

things – something I've given a lot of thought to over the years –

and I was struck by how much tosh there was in it! It's all very

convincing with lots of long words and pyschobabble but in the end

these are all assertions. This is not scientific. You cannot say that

because some collects this that they are anally retentive. I'm always

suspicious that the longer the sentence and the more complicated the

words the less the meaning there is. There I was eating my supper in

the hotel writing “RUBBISH!” Ha!

I

actually think this quite funny. Is this on exhibition somewhere?

AB: I

do exhibit the Museum yes; last year in Chicago and a solo show

coming up in Blackpool. I show them as the images. The only time I've

shown the actual rubbish was my own Hoard which was every item of

rubbish from my art practice that I collected during 2012.

LT:

What was the name of the artist that took all of his own stuff and he

shredded everything?

AB:

Michael Landy. Break Down (2001).

LT:

Yes. Which is the same sort of area isn't it?

AB:

Yes, definitely. I'm studying other artists' use of rubbish and he's

one of the more well known artists through media prominence. It was a

big statement to make. He destroyed absolutely everything he owned

including other artists' works he had collected.

LT:

It's fascinated stuff. Ordinary people reading the paper will say

“this is not good!” and actually there is some serious stuff in

there. I did archaeology so I've been specialising in rubbish! But of

course it acquires a different status once it's old there is that

sort of nostalgia what I call nostalgia effect.

AB:

And rarity too.

LT:

Yes. We could talk about that for ages but sadly we don't have time

today. I'll take a photo of this. I might use this because at the end

of the day I'm going to blast some images at 4-5 o'clock and I might

just show one or two things that came in and this has got to be in. …

I don't know what else I can say about this that you don't already

know.

AB:

I'd like to hear what you think of it's value.

LT:

You don't really want to know that?

AB: I

do. By the process you'd normally use to value objects..?

LT: Oh

that's easy. The process by which we do all the valuations works on

the basis that most of the objects brought in are comparable to

similar items. In the case of ceramics for example; ceramics are mass

produced essentially identical objects will appear over time with

little variants.

AB:

So, stuff like this [rubbish] is the extreme of that mass-production?

LT:

It's interesting; if you'd been in something like the Turner Prize

and this had been made by someone who had a name already as a

conceptual artist it would have a value which you could probably

gauge. The artist would have an agent which would already be tapping

into New York probably.. but what it's worth is what anyone is

prepared to pay for it. It's a really good question. I would say it's

worth, monetarily, in this present market, erm, it's probably worth

somewhere between nothing and nothing plus X.

AB:

Haha!

LT:

That's all I can say! But when you come back in five years time

having won the Turner Prize with one of these it'll have a value.

It's a question of finding people who are prepared to pay for it.

AB: So

I need someone to externally validate it?

LT:

The answer to your question is Tom

Sawyer by Mark Twain. Tom Sawyer was painting a fence as

punishment and all his chums come up the hillside and they say, “Ha

ha ha! You were made to paint the fence!” And Tom says, “You

haven't been asked to paint the fence have you?” Tom's making them

feel jealous about this painting the fence and in the end they're

desperate to paint the fence, which is a punishment basically, and

Tom says “What are you going to give me if I let you paint the

fence?” And so they end up taking coins out of their pockets and

bits of orange peel and all the sorts of things that school boys have

in their pockets in Mississippi in 1880. Gradually he's building up

this treasure trove of rubbish and they're all objects that they've

given up because they want to paint the fence. He's turned the fence

painting from a punishment into something desirable and it's

transacted with the stuff they have in their pockets. That's the only

answer I can give! It's worth a painted fence!

AB:

Great! Thank you very much.

|

| Photo courtesy The Hepworth, Wakefield |